The space your child plays in can ask questions.

Your child is engaged in a dialogue with the room and the materials. The furniture you use and the toys you offer have a direct effect on what learning takes place. Followers of the Reggio Emilia Approach call this idea the environment as the third teacher.

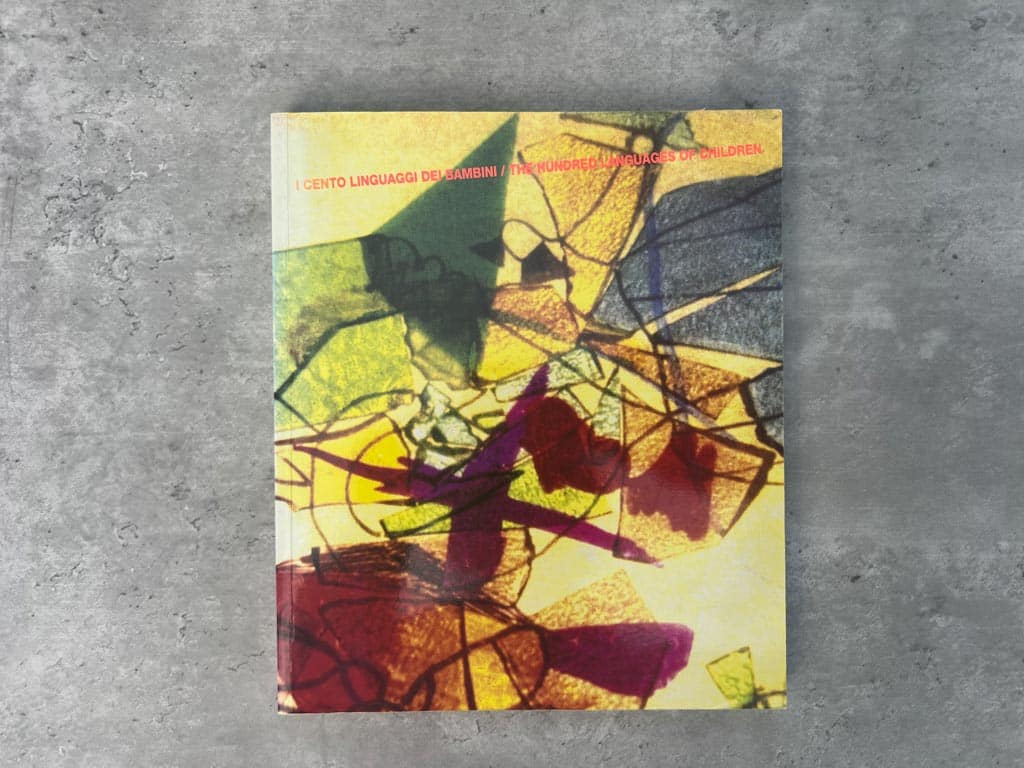

The preschools of Reggio Emilia are designed to have a ‘piazza’, a space in the middle of the building where children can encounter each other, to meet on their way from one room to another. This encourages conversation promotes language development. Compare this to a nursery where each class has its own private garden, where the babies, toddlers and preschoolers never meet.

What would be the result of putting a stage in your playroom? What kind of play would it encourage?

What does it say to your child if you give them easy access to pencils and paper? What does it say if you don’t?

If you only ever offer closed-ended materials such as puzzles, or electronic toys that entertain rather than challenge, how will your child learn to problem-solve? Difficult tasks promote creativity and perseverance. Your playroom should be full of these.

This is the topic that has interested me more than any other in early years education. It was the focus of masters dissertation, and it’s an ongoing passion. One reason is that I simply don’t have the time to ‘educate’ my children at home, to hover over them, offering direct instruction. Another is that I don’t believe this is a natural state of affairs. Children like to play apart from adults, to make their own discoveries and their own fun. It’s why 100 Toys focuses on open-ended toys and why I wrote the guide to independent play.

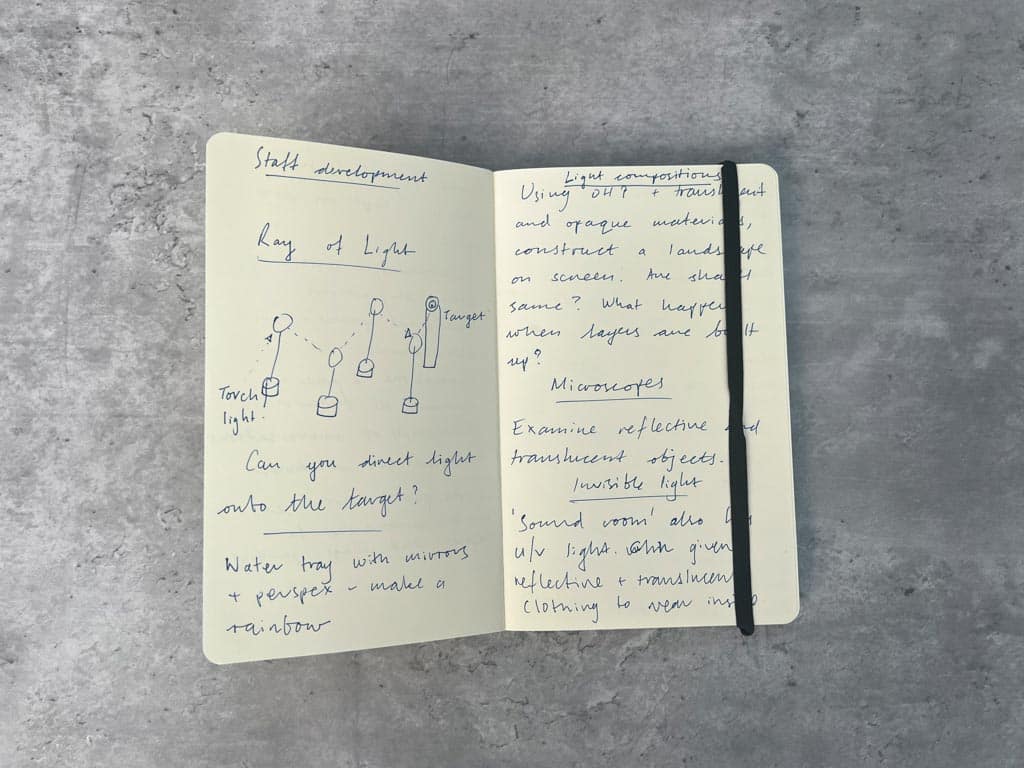

What change could you make to the environment today to encourage a new type of play?

Read more about the Reggio Emilia Approach and how you can use provocations to extend your child’s play.